Is the horror genre feminist or foe?

Is horror the only genre pushing the boundaries when it comes to telling women’s stories onscreen?

I’ve got a theory. As my recent post detailed, I am something of a horror fan. And in the many years I’ve been watching scary movies, I am struck by the ways that women are represented in them. Not just that, but the sheer volume of women represented in horror above all other genres.

[Spoilers ahead as well as discussions and imagery around violence and gore.]

So I decided to do a little digging. My conclusion is that horror is one of the few cinematic genres that is truly pushing the boundaries when it comes to female representation. While those representations are not always completely unproblematic, it’s interesting to me how truly unexpected and weird that is when we consider that horror is so often associated with the male gaze…

Could it be that horror is one of the few genres which experiments with gender roles, champions complex female characters, employs female performers of all ages, and produces storylines which centre around something other than motherhood, marriage, or romance? Or is this just wishful thinking from a horror-obsessed feminist wanting to absolve the genre of its past sins?

For my fellow spooky girls who love a scary movie, this post is for you.

Horror and The Bechdel Test

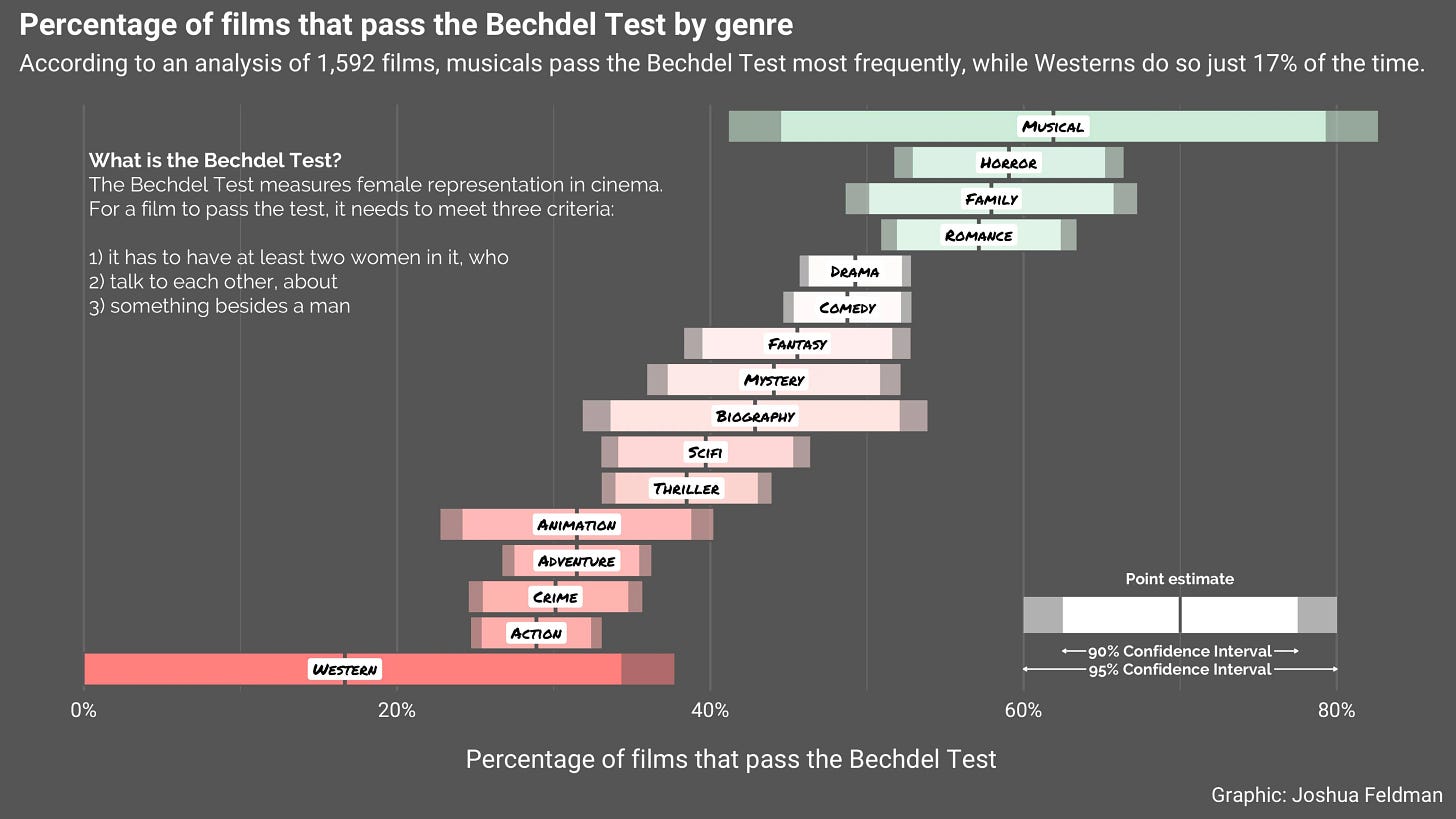

Many of you will be familiar with the Bechdel Test (or as my husband calls it, ‘That Lasagne test’.) This is a test that measures representation of women in film. The criteria is as follows;

There must be at least two women featured (some versions of this criteria insist that these must be named characters.)

The two women must talk to each other onscreen.

The onscreen conversation must discuss something other than a man.

The genre for which the most films passed this test were musicals. Horror was second with a pass rate just below 70%. For horror to surpass the less niche themes of drama, romance, and action really says something. We tend to stereotype horror as primarily being made for men, by men - but in meeting the criteria of the Bechdel test, among other things, it suddenly makes more sense why they are so many female horror fans out there.

There are some interesting dynamics to this. In Carol Clover’s ‘Men, Women and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film’ she presents the idea that voyeuristic roles are reversed in horror, forcing the viewer to sympathise with the ‘submissive’ character - usually a woman. This is much less common of other genres, so perhaps is one of the few instances where an audience of all genders is expected to identify with the female protagonist - and one of the few where women can fully identify with a character more like themselves.

When turning this over to the horror film, as in the traditional slasher film, the spectator assumes a submissive position whenever they identify with the female victim, and more importantly, the female heroine (the Final Girl). - Donata Totaro, The Final Girl: A Few Thoughts on Feminism and Horror | Offscreen.

Does this make horror truly feminist? What is horror doing for women onscreen that other genres aren’t?

👍Feminist: Female-led storylines

It’s odd to talk about the existence of female protagonists as a radical act, but it does feel significant to mention that women are still rarely the main characters when it comes to literature or cinema. It’s easy to reel off female horror characters because they are in abundance. Laurie Strode of Halloween, Reagan McNeill of The Exorcist, Alien’s Ellen Ripley, Carrie, Rosemary’s Baby - many of these horrors are five decades old and yet have female characters at the centre of them.

We even get the luxury of all-female casts in some cases - for example, 2018’s Suspiria, and The Descent. What’s more, is that many of the characters are three-dimensional and fleshed out. Yes this should be a baseline requirement, but women in film are often notoriously stereotypical, prop-like, or only present to progress the story for the other, more rounded, male characters.

The women in horror movies are complex, with varying motives, desires, and flaws - which can only be a good thing.

👎Foe: Outdated tropes

The most significant discussions around feminism and horror hinge on the tropes that still plague the genre.

During the 1970s, when slasher flicks were all the rage, women were nought but cannon fodder, and were killed off in increasingly gruesome ways, often through a sexualised lens. ‘The Final Girl’ concept emerged - the idea that the most ’pure’ and ‘innocent’ women among a group would fight for survival.

The concepts of the vamp and the virgin appear in various forms across countless titles - the idea that the liberated, sexually empowered women will be punished and suffer, while the innocent virgin will be spared. In The Descent, the woman who is revealed to have betrayed the main character by having an affair with her husband is positioned as a treacherous seductress, deserving of her fate. The main character, on the other hand, is painted as a tragic victim and survivor through her connection to her husband and daughter.

As a side note, the ‘mother’ archetype itself is also a frustratingly unsympathetic and often repeated theme - that women who are mothers ‘have more to fight for’, and are somehow more deserving of survival. Their maternal nature is positioned as a virtue and is given as the sole motivator for their characters. Their task is often to selflessly protect their children and not themselves, playing into the idea of motherly self-sacrifice being the only thing that can overcome evil.

I don’t think I need to point out how problematic and archaic it is to attach a woman’s value to her virginity OR whether she possesses the ability to have a child… Yet we still see this reflected in movies from Alien 2 (with Ripley and Newt’s relationship) to the more recent Evil Dead Rises, and to a lesser extent, films like The Conjuring, Us, or The Babadook where the mother and her children are the focus of the paranormal entity.

But it’s not just victimhood that defines female characters in horror.

‘The Psycho Biddy’ (which scholars Peter Shelley and Tomas Fisziak link back to 1962’s ‘Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?’) is described as a formerly glamorous woman who has grown old, (usually) unattractive, mental unstable, and cruel in nature. She has become a lasting presence across the decades, and one that doesn’t seem to be going anywhere just yet. In fact the ‘gruesomeness’ - no, mere existence - of an ageing woman, is played for shocks and scares.

This is more explicit in contemporary films like X (2022), Pearl or older titles like Onibaba (1964), but shades of it exist within the ideas around witches, sorceresses, and women operating in occult spaces. Narratives usually centre around these women looking to regain their youth (a popular myth attached to stories of witchcraft), or those looking to punish or seek vengeance on others out of bitterness and jealousy.

It’s also no coincidence that women who are somehow connected to something otherworldly are shown as dishevelled eccentrics, or impossibly beautiful - but usually criminally insane.

👍 Feminist: Subverting expectations

While the tropes exist, there is more room within the horror genre to subvert cliches and create something unexpected.

Perhaps the most famous example is Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Thinking back to the cheesy, B-movie grade Hollywood adaptation starring Kirsty Swanson, rather than the ground-breaking TV series starring Sarah Michelle Geller, the concept of Buffy was conceived to ‘subvert’ the trope of the screaming female victim.

Joss Whedon famously took the pretty blonde girl, too afraid to go out at night, and made her into a monster-killing machine that demons feared. The series has perhaps survived the test of time because it has turned the genre on its head and spawned a generation of similar ideas.

Buffy is not even ‘a final girl’ in the typical sense - she is a force to be reckoned with. The show had so much fun exploring this from what it’s like to balance the every day life of a teenage girl (from boys, to besties, high school and prom) and what her slayer status means to the people around her - including the men in her life, some of whom live in the shadow of her power.

Buffy was not the first character to revolutionise horror, but we see echoes of Buffy in movies like The Craft, The Mummy, and The Witch and in newer titles like Fear Street, and the Scream reboot. These women are not weak, meek, or scream queens - they go down fighting. They use their power, intellect, and cunning to beat the baddie. They do not cower behind their male peers. They are independent, resourceful, and powerful.

👎Foe: Presence of female horror directors

While representation is present within cast and characters, there is a sparser, and less acknowledged number of female directors within the genre. And there are certainly challenges with having female characters - supposedly ‘relatable’ for women - written by men.

While Anne Rice, Angela Carter, and Mary Shelley are widely celebrated in horror literature, (and have been for quite some time) cinema has had some catching up to do.

It’s not that female horror directors don’t exist, but they still don’t quite have the household name status as, say, Wes Craven, George Romero, or John Carpenter.

But things are changing - again, perhaps moreso than within the wider circles of Hollywood. Jennifer Kent (The Babadook), Ana Lily Amirpour (A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night), Rose Glass (Saint Maud), Karyn Kusama (Jennifer’s Body) and Anna Biller (The Love Witch) - plus a whole host of lesser known female ‘indie’ directors - are becoming more widely acknowledged and celebrated.

One could also argue that their films are markedly different in tone compared to those directed by men; exploring themes like friendship, sexuality, parenting, mental health, religion, and romance - as well as being much more intersectional in their exploration. They also don’t romanticise or sexualise their characters in quite the same way. And yet they aren’t treated as a separate sub-genre of their own. There is no ‘women’s horror’ category - their work stands perfectly equal.

👍 Feminist: Feminist subtexts

Horror, and its close cousin, sci-fi are often layered with subtext, allegories, and metaphors for more tangible ‘real’ concepts. This is partly what makes them so enjoyable.

Here, we get to explore fantasies about female power, revenge and survival through the supernatural and the uncanny. There are lessons to be learned.

A notable example is Ari Aster’s Midsommar. Shortly after watching it for the first time, an old work friend messaged me and asked me for my interpretation of it; what did I think of the ending? It turns out that there are two different ways the film tends to be interpreted, and it largely depends on your gender.

Both of us viewed it the same way. In being crowned as the May Queen, Florence Pugh’s deeply troubled character finds people who finally support and accept her. The men in her life are punished for their misdeeds. The alternative interpretation rests more on the horror element - that Pugh is now trapped with a murderous cult, who have tortured and killed her friends.

This is what’s great about horror, because much of the ‘fear’ rests on what happens when women are, or aren’t in control. If we look at films about witches specifically, the entire premise rests on the idea that women with such power are evil and terrifying. The horror lies in what powerful women choose to do with that power.

In Suspiria, they manipulate and sacrifice the innocent. In Death Becomes Her, they seek eternal youth and plan to live forever. In Drag Me To Hell, they place curses on people. In Last Night in Soho, they kill.

There’s also an idea of ‘reclaiming’ power for good. This is explored in In I Spit in Your Grave, where a woman exacts righteous revenge on the men who raped her in the ultimate ‘justice’ fantasy. In Ready or Not, the main character quite literally fights back against the oppression of her new family, and their ‘ownership’ of her via marriage.

Very few other genres explore the idea of a dangerous and empowered women in such a variety of ways. These characters refuse to comply, to conform, or to accept social constructs as they are. Whether the source of their power is supernatural or not, the fact they have it is significant.

👎 Foe: The female body in the horror universe

Women’s bodies within horror are still a much debated topic. While human bodies, on a whole, get a pretty hard time within horror, women’s bodies have generally bore the brunt of nastiness.

Particularly in earlier films from the 1960s and ‘70s (which I am keen to point out, coincide with periods of social upheaval and female liberation), women’s bodies were objectified by violence. There was also plenty of psychological suffering tied to trauma - something I’d argue is far less explored with male characters.

In both The Exorcist and Rosemary’s Baby, young women’s bodies are violated and used, against their will, as vessels for evil. In Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Halloween, and The Silence of The Lambs, it’s predominantly female bodies that are stabbed, gutted, and dismembered. The Hills Have Eyes (a film which I vehemently despise) features a brutal rape scene, while even classics like The Evil Dead, Eyes Without a Face and Pet Semetary build their ‘horror’ around the corruption, violation, and mutilation of female bodies. This ‘others’ them, making them seem less human, and of course in some cases, still not quite in the full control or ownership of the female character.

This extends to more contemporary sub-genres too, dubbed ‘torture porn’, within franchises like Hostel and Saw.

Yet violence isn’t the only way that women’s bodies are disrespected and misrepresented. The idea of change or transformation is represented onscreen through mutilation, disfigurement, or ageing - and these are often used as shorthand to depict women as monstrous.

Physical appearance - and perceived ugliness - is inextricably linked to evil nature. Though this is not reserved solely for the women in horror, much of these ideas remain in titles like Barbarian and The Visit.

The verdict

Horror on the silver screen has a lot to answer for when it comes to past crimes. Some of the stigma and imagery remain today but are fast falling out favour. My own view is that has horror come a long way and it’s quite possibly the most promising and exciting landscape for female creatives.

It also makes it clearer why so many women, like me, connect with the genre. But is it the most feminist genre? I guess time will tell…

Read more on this topic…

Tell me what you think in the comments… Or just tell me about your favourite horrors.